I’m trying to remember when I first heard about it. It was in 1980, I think, before it began making headlines. I was married then to a woman I loved and with whom I enjoyed a robust sex life, which nevertheless couldn’t keep me from seeking pleasure with men occasionally, when I dared, which was rarely. But it did sometimes happen. I had to sneak away to find it and it had to be done when I was drunk, anonymously. I couldn’t face the truth of my nature in any other way.

My wife wasn’t concerned about what she thought of as my earlier homosexual experiences. She considered them firmly, as I did nervously, to be an adolescent thing, a neurosis, some kind of spooky response to stress, and even now I won’t say that she was wrong. She wasn’t interested in men and their ways. A horsewoman, privately schooled, she had been raised in a family that treasured its daughters and put their brothers to mucking out the barn. She scorned all conventionally female roles and assignments; she wouldn’t pick up a sock from the floor if she thought it belonged to me. But as long as we were lovers, physical together, we could agree I was in the right place.

In one of those summers before Anastasia was published, anyhow, I was at home reading The Village Voice on a bright afternoon. Was she there? I don’t remember. I read the Voice every week faithfully because I loved its columnists – Alex Cockburn, Nat Hentoff, Arthur Bell -- and because there were ads in the back promising sexual pleasures as yet beyond my experience, ads for parties, escorts, and bathhouses, in particular, where one might mix with multiple men at once. I had never dared to do it, but on this day the thrill in my stomach was too intense to be put down. Quickly after, I arranged to meet a literary agent in New York and passed an afternoon at the Ansonia Baths on 72nd Street, my first adventure of that kind. A nice man looked after me and, because I wasn’t drinking, one was enough.

I can’t say if I was infected with HIV on that day exactly – because it could have been sooner and it could have been later – but I mark it from there for myself, owing to the way the peril suddenly rose up around me and because the date concurs with the known course of the virus in destroying the immune system: five to ten years, it was suggested then, from infection to collapse, as my system did in 1989.

The following spring I was in Boston, finishing research for Anastasia at Harvard; at the last minute, a new trove of papers opened up. I stayed briefly at a hotel on Boylston Street and on my first night there went to the baths for a second time. I remember only darkness and confusion from that night. I didn’t understand the nature of such places and wandered heedlessly through the hallways and cubbyholes, leaving the door to my own room unlocked and untended for more than an hour. When I returned, my wedding ring was gone, stolen from my trousers. I had taken it off to speed things up, probably, and distance myself further from reality.

Now I was trapped, caught in the act. No amount of rationalizing would cover a blunder like this. I made up some story, something about itinerant maids in the hotel, who must have lifted my ring from the sink in the bathroom after I took a shower and forgot to replace it – as if I had ever taken my ring off for a shower!

I don’t think my wife was fooled, but, as I said before, I don’t think she cared very much. She joined me in Boston for several months, aimless and depressed. We took an apartment on Marlborough Street and tried to live as adults; she wanted to do some acting in local theatres but never pulled herself together for it. I knew even then that her behavior was typical of alcoholic marriages when the drinking partner lays off the sauce, as I did that whole spring. When I was up, she was down. When I did well, she took to her bed, and when I was drunk and ashamed of myself she leaped to her feet with notable energy. I had another wedding ring made, a simple gold band like the first, just in time for the divorce.

But in Boston I noticed something – that, having burned one of my fingers by picking up a cigarette from the wrong end, lit, it took weeks for the sore to disappear. At first it was just a blister, the kind you’d expect if that happened. Then it spread further up and down my finger, broke open, and turned into a deep and painful wound, leaking blood. In the Voice, I saw Arthur Bell’s reports about a “gay cancer” spreading in New York, and it took me no time at all to conclude that my sins had caught up with me in a justly horrible way. I told myself, “Something is very wrong here.” Then Anastasia was published, and everything changed.

***

I was sober after that for more than a decade, from 1982 to 1994, and throughout the production of my second book, American Cassandra. This was a biography of Dorothy Thompson, “First Lady of American Journalism” and the wife of Sinclair Lewis, Nobel Prize-winning author of Babbitt, Main Street, Dodsworth, and Elmer Gantry -- a notorious drunk, “not `a heavy drinker,’” as I explained in the book, “not `an artist’ with an artist's need for quick release, but a full-blown alcoholic, whose benders, brainstorms, and furniture-smashing sprees were known to literary society across the United States and Europe.” Dorothy kept their marriage going for thirteen bloody years before resigning, defeated, just after Pearl Harbor in 1941. “In the end all women left him,” she reported, “driven away perhaps by the impossibility of penetrating the curtain that screened him from all real intimacy.”

I had stumbled into the world of American letters unexpectedly, following the advice of my editor in London: “Peter, write what you want to write. That’s all there is.” During my adventures in Spain with “La Pasionaria,” I encountered the works of an American journalist, Vincent Sheean, who, with Hemingway, Herbert Matthews, Martha Gellhorn, Louis Fischer, and many others, had chronicled the Spanish Civil War for American newspapers, urging readers in the heartland to wake up to the menace of fascism.

That is putting it simply. Sheean was one of the last American correspondents to leave Spain as the Republic collapsed in 1939, seeing in the valor of the Republican cause “a common conscience” to galvanize democracy against the dictators. The war in Spain was no “dress rehearsal” for World War II, he warned, but already the opening battle: “Spain alone had resisted and was still resisting the limitless claims of Fascist imperialism; Spain alone raised its clenched fist against the bombs.”

I easily fell in love with Jimmy Sheean – James Vincent Sheean, called Jimmy by all who knew him – the most earnest, and, I may say, “literary” of the U.S. reporters who went to Europe after World War I and made it their beat. Tall, handsome – “He may have been the handsomest man I ever met,” a male colleague confessed -- astonishingly literate and articulate, he had been born in Pana, Illinois and left it as soon as he could, moving first to New York, where he took up with Edna Millay and the “bohemian” crowd in Greenwich Village, and then to Paris, Rome, China, Madrid, Berlin, Morocco, London, and Palestine, where an outbreak of violence between Jews and Arabs in 1929 was enough to give him a nervous breakdown.

It wouldn’t be the last. Sheean’s character was routinely described as “Irish,” but more nearly clarified by his abundant use of alcohol and his ultra-sensitive nerves. He was undoubtedly bipolar, with “a Celtic capacity for wonder and worship” that his friends learned to accommodate in the interest of keeping him safe. He had an uncanny ability of turning up at exactly the right moment wherever news was being made, and was “psychic” to a point that his colleagues all believed it. In 1948, he had rushed to India in the belief that Gandhi was about to be murdered and stood just twelve feet away when the Mahatma was gunned down by a Hindu nationalist.

“It is easy to dismiss him as a `crazy Irishman’,” said Dorothy Thompson, “`Byronesque,’ or even `Megalomaniac,’ when he asserts that he foresaw the assassination of Gandhi and, present at the event, underwent a devastating experience, including the appearance of blisters on his hands. It happens, however, that there are witnesses to both phenomena.” Sheean’s famous memoir, Personal History, published to world acclaim in 1935, was the winner of the first National Book Award for Biography and transformed the conception of foreign correspondence in the United States. Journalists from that moment forward modeled themselves on him. His style wasn’t easy to classify. “It is a sort of semi‐autobiographical political journalism,” he said, “ — the external world and its graver struggles seen from the point of view of an observer who is not indifferent to them.” Mary McCarthy reviewed the book for The Nation:

The young man who reveals himself in this autobiography is certainly no ordinary journalist, but neither is he a professional adventurer. He is a human being of extraordinary taste and sensibility, who throughout 15 years of turbulent experience has been primarily interested in moral values. Violence and catastrophe per se have not attracted him, but he has found that in scenes of crisis the current of human affairs runs clearest. His book is only incidentally a chronicle of events; it is, at bottom, a serious study of the relation of an individual to the world. Sheean’s clear-sighted perception of this problem, his peculiar, passionate approach to it, turn a lively, well-written piece of journalism into a first-class literary work.

Vincent Sheean by Barbara Ker-Seymer and John Banting

A large part of Personal History is given over to Jimmy Sheean’s doomed romance with Rayna Prohme, an American intellectual from Chicago who had attached herself to communism and the Nationalist movement in China under Sun Yat-sen. Sheean met her in 1927 in Hankou, where Chinese leftists had fled after a crackdown by the government of Chiang Kai-shek. Rayna was a de facto agent of the Soviet Union, working for the Comintern, and, to Sheean, “a marvelously pure flame” of dedication and compassion, “incandescent” with revolutionary ardor. Described by another reporter as a “red-headed gal, spitfire, mad as a hatter, complete Bolshevik,” for Jimmy, Rayna was Beatrice in Paradise, the red of her curls casting auras and haloes wherever she walked in the service of humanity.

“She had decided that life was not possible for her on any other terms,” he wrote; “that she could not bear the spectacle of the world under its present arrangement, and that her place was within the organisms struggling to upset and rearrange it.” They were together in Moscow when Rayna suddenly died of encephalitis, six months after their meeting, forever sealing Jimmy’s adoration and remorse. They had not been lovers — Rayna was married to someone else — and Jimmy wasn’t a communist, then or later. But he saw in Rayna Prohme some ideal of womanhood that took over his mind and spoiled all his romantic relationships after that. He went off the rails with grief, drinking, rages, and depression, an extended “shemozzle” of the kind his friends came to recognize and prepare for as he moved, always writing, through the 20th century.

In 1935, as Personal History swept him to fame, Jimmy married Diana Forbes-Robertson, always called “Dinah,” youngest daughter of Britain’s great Shakespearean actor-manager, Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson, “the Hamlet of his day”; and niece of Maxine Elliott, American beauty and stage star, businesswoman, society diva, and intimate of princes, politicians, and world financiers. Dinah was 20 at the time of her wedding and had known Jimmy Sheean only scantly for several months. “It must have been one of the quickest proposals and acceptances ever,” she admitted. They would divorce in 1946 and remarry in 1949, separating after that again for many years, reuniting, and ending together in Italy, contentedly, for the last years of Jimmy’s life. “I knew nothing then about anything,” Dinah said. “Writers have no time for marriage.”

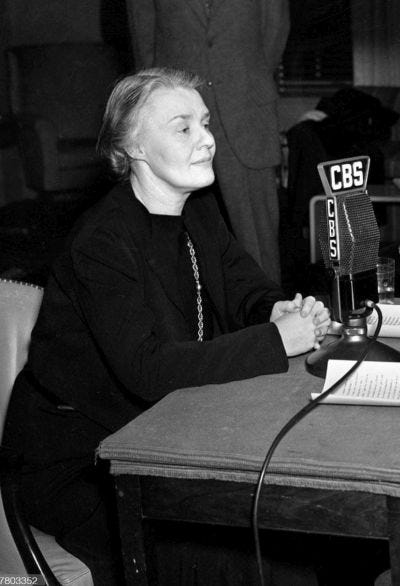

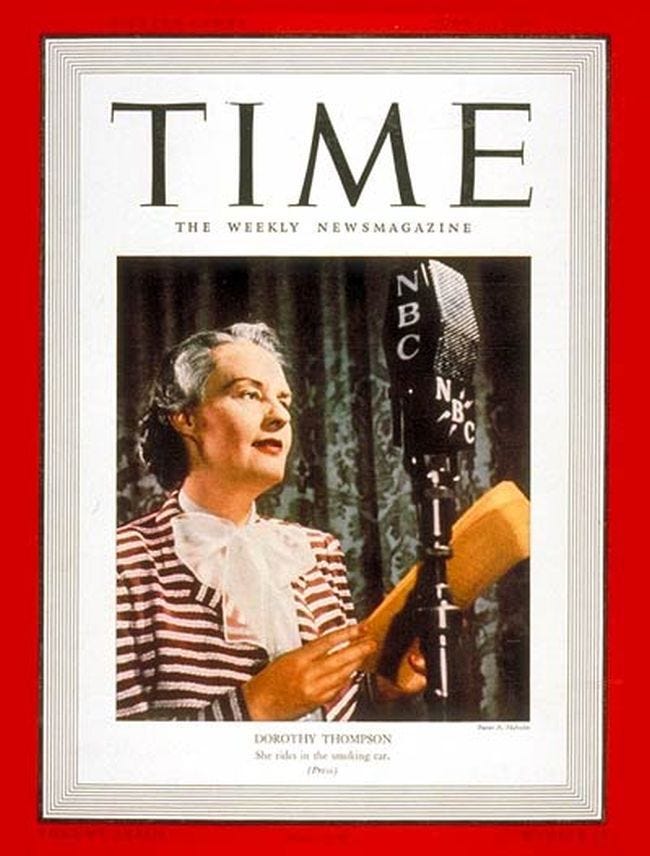

All this I learned later, after I came back to Vermont from the Spanish disaster and Jimmy led me to the woman of my own ideal: Dorothy Thompson, journalist, columnist, lecturer, broadcaster – “Stern Daughter of the Voice of God,” as Jimmy called her, quoting Wordsworth’s “Ode to Duty.” Dorothy was the first American reporter to be booted out of Nazi Germany on Hitler’s order, “the most influential woman in the United States after Eleanor Roosevelt,” according to Time magazine, which had featured her on its cover in 1939. The daughter of a Methodist minister in upstate New York, she had been active in the women’s suffrage campaign and in 1920 went to Europe to report the news, freelancing, with no official assignment. Her stories soon won her a contract with the Curtis-Martin newspaper syndicate, publishers also of The Ladies Home Journal and The Saturday Evening Post, and within three years she was chief of its Central European bureau, with headquarters in Berlin.

“I had nine countries to cover," Dorothy remembered, "over an enormous territory, each one of them with a different history and problems. I had no assistance, not even a secretary." Nothing like the prestige and high seriousness of a later age had as yet adhered to foreign correspondence or to newspaper work in general; it was loosely considered to be a profession for “gadflies,” “public and private nuisances,” as Dorothy said, “with whom the less one had to do the better.” She was among a small band of American adventurers, overwhelmingly male, who gave weight to the enterprise, and in later years she always included her colleagues in gratitude for her success: John Gunther, Jimmy Sheean, H. R. Knickerbocker, Jay Allen, Edgar Mowrer, and many others, all lifelong friends and, in some cases, part-time lovers.

After marrying a Hungarian Lothario who betrayed her with multiple affairs, Dorothy Thompson met Sinclair Lewis and in 1928 returned to the United States as his devoted wife, a role that didn’t suit her. She had a baby, a son, Michael, which also didn’t suit her. Lewis won the Nobel Prize in 1930. They bought a farm in Vermont with two houses on it – “Twin Farms,” in Barnard, now an obscenely expensive millionaires’ resort – while Dorothy continued writing and traveling, chronicling especially the ominous rise of the Nazis in Berlin. After her expulsion from Germany in 1934, an event that made her famous, she began a newspaper column, “On the Record,” appearing three times a week opposite Walter Lippmann in the New York Herald Tribune and syndicated widely. She had millions of readers and a vast radio audience. She was the highest-paid lecturer in the United States, “dean of newswomen," "the greatest journalist this generation has seen in any country,” John Gunther proposed, “and that is not saying nearly enough." And I had never heard of her -- rather, I had heard of her in the wrong way, glancingly, as Sinclair Lewis’s wife.

Here’s how it happened: In 1985, I was again at the library, still searching, looking for something to carry me forward and wondering if a biography of Vincent Sheean had been published since his death ten years before. Many of his books were there: Personal History, of course; Not Peace But a Sword, Between the Thunder and the Sun, Lead, Kindly Light – about Gandhi – The Indigo Bunting – about Edna St. Vincent Millay – and, lastly, Dorothy and Red, published in 1963, Sheean’s portrait of the Lewis-Thompson marriage and his relations with them both.

Why did I pull down that book in particular? How did I know nothing about Dorothy Thompson other than what I had learned for a college paper about “Red,” Sinclair Lewis? She had turned up, disguised, in Dodsworth (1929), and again in Gideon Planish (1943), after the Lewis marriage ended and he satirized her as “Winifred Homeward, The Talking Woman.” He was wonderfully cruel about it:

She was an automatic, self-starting talker. Any throng of more than two persons constituted a lecture audience for her, and at the sight of them she mounted an imaginary platform, pushed aside an imaginary glass of water, and started a fervent address full of imaginary information about Conditions and Situations that lasted till the audience had sneaked out -- or a little longer. …

Winifred was as handsome as a horse, a portly young presence with a voice that smothered you under a blanket of molasses and brimstone. … She was something new in the history of women, and whether she stemmed from Queen Catherine, Florence Nightingale, Lucrezia Borgia, Frances Willard, Victoria Woodhull, Nancy Astor, Carrie Nation or Aimée Semple McPherson, the holy woman of Los Angeles, has not been determined. … She had the wisdom of Astarte and the punch of Joe Louis, and her eyelids were a little weary.

So — who was Dorothy Thompson? I opened Dorothy and Red and started to read. It had been a huge success on publication, both praised and reviled for its – in 1963 – frank revelations of marital discord, charting Lewis’s alcoholic decline and Dorothy’s “sapphic” adventures with a German sculptor and writer, Christa Winsloe, author of Mädchen in Uniform, a cinema sensation of 1932 and an enduring landmark of lesbian sensibility. Christa was the divorced wife of a Hungarian baron, whom Dorothy had known for several years before noticing her at all, at a Christmas house party outside Vienna. It was meant to be a skiing holiday for the Lewises and their friends but devolved into a tension-ridden fortnight without snow, the anxiety heightened by Sinclair Lewis not drinking while everyone else did, to excess. Girls in Uniform, about repressed adolescents and their teachers in a strict Prussian boarding school, was based on Christa Winsloe’s own experiences and speaks for the sexual longings and freedoms of Weimar Germany before Hitler stamped them out. Dorothy, to her great surprise, fell deeply in love with her. She kept a diary of that holiday on the slopes:

So it has happened to me again, after all these years. It has only, really, happened to me once before. ... The soft, quick, natural kiss on my throat, the quite unconscious (seemingly) even open kiss on my breast, as she stood below me on the stairs ... Immediately I felt the strange, soft feeling ... curious ... of being at home, and at rest; an enveloping warmth and sweetness, like a drowsy bath. Only to be near her; to touch her when I went by. … `Don't go away.' I wanted to say, `Don't go.' … Her name suddenly had a magic quality. C[hrista]. I wanted to say it. To use it. … I love this woman. There it stands, and makes the word love applied to any other woman in the world ridiculous.

Dorothy’s affair with Christa Winsloe lasted for three years as her marriage to Lewis disintegrated. Christa joined them intermittently in New York and Vermont, forming an uneasy threesome, but finally returned to Europe for good in 1935. She was killed in World War II, shot “by mistake” as the Nazis evacuated France. Nothing suggests that Dorothy was “lesbian” after that, or ever had another romantic relationship with a woman. “Mir passt es auch nicht,” she wrote in her diary. “Ich bin doch heterosexuell.” (I don’t like it, anyway. I am heterosexual.) She was at pains to reassure Red at one point, while staying with Christa in Italy, that their love was platonic. Christa was just "the most sympathetic woman I've met in years and years," said Dorothy: “As for your last admonition to me -- do you remember it? -- have no fears, I ain't thata way." And still she turns up on lists of historical figures who were “secretly homosexual,” which is the only other way I had heard about her before I started my research.

How stupid those things are, those puffed-up lists: “Ten Famous People You Never Knew Were Gay,” and so on, bringing to the fore some aspect of personality and presenting it as final fact. Some years after my book was published, I gave a talk in Palm Beach and was harangued by another biographer in the audience, Blanche Wiesen Cooke, whose books about Eleanor Roosevelt purport to expose a similarly definitive lesbianism in her heroine: that of an intelligent woman, committed and involved, among the first generation of fully educated and emancipated women in America, looking for the tenderness and intimacy she lacked in a difficult, high-profile marriage. Cooke accused me of having “abandoned the issue of Dorothy’s lesbianism” in my book.

“Hold on,” I said, in a moment I’m proud of. “I didn’t abandon it. She abandoned it.” In the end, Dorothy Thompson was married three times, finally to a Czech painter, Maxim Kopf, with whom she enjoyed not just a quite raucously physical relationship but who was, as she insisted, “the man I should have married in the first place.” I have no doubt that a woman writing her story would have told it differently than I did. But as I began to read, to go deeper and deeper into Dorothy's life, it pained me to think that her unique and magnificent legacy – to women, to journalists, to everyone – should be reduced to a sapphic bent.

That we know of Dorothy’s lesbian excursion at all is thanks to Jimmy Sheean, whose own sexual conflicts became apparent as I progressed. His affairs with men were infrequent but intense, known to some and not others, reflected in his wife’s notable frustration, and never revealed in his writing, public or private. Alcohol, normally, was the galvanizing agent in Jimmy’s “particularly shaky sexuality,” as Dinah Sheean called it, “the one unmentionable subject.” I related to him fully. Whether repressed emotions and passions contributed to his decision to publish the full details of Dorothy’s affair with Christa Winsloe, as a mark of solidarity or some kind of substitute confession, it is of course impossible to tell. But one thing that drew me to him from the start was his unaccentuated masculinity, his complete lack of laddishness and misogynism. Male he was, but with none of the swagger or strong-man posing so many of his colleagues adopted in a profession still famous for them. Jimmy Sheean’s spirit, I submit, was above gender, and his spirit was the substance of his work.

After her death in 1961, Dorothy Thompson’s archive had gone to her alma mater, Syracuse University — 150 cartons of papers, consisting of family records, hundreds of manuscripts, columns, and published articles, personal diaries and letters, photographs, different research files, and the incoming and outgoing correspondence of a 40-year career at the highest levels of international politics, journalism, and the arts. A contract between her book publishers, Houghton Mifflin, and the Thompson estate called for an authorized biography, and Jimmy was given first crack at it. He published her diary about Christa Winsloe unedited in Dorothy and Red. He claimed to be “startled” by the discovery, because in life Dorothy “was a reticent woman about personal matters” and no suspicion of lesbianism had crossed his mind in regard to her.

“At first, I couldn’t decide whether she wanted the story told,” Jimmy wrote. “Yet she had left the papers for any student to read; many had been annotated and corrected in her own handwriting, as if she had been preparing her autobiography before her death.”

In fact, she was. She envisioned her own “Life and Times” on a massive scale, but the project defeated her, as it did Jimmy too, when he got into it. He was a novelist manqué in his own estimation, forever swearing off journalism until the pressure of empty bank accounts sent him hurrying back to editors. But in Dorothy’s case he had leaped too quickly. The magnitude of her enterprise and thoroughness of her recordkeeping “scared him half to death,” said Dinah, his wife. “He was stunned. Dorothy had kept everything.” So he wrote his book as a memoir, focusing on the fourteen years of the Lewis marriage and including himself prominently in the narrative. That its most remembered feature would be the lesbian interlude distressed him, as it did me, and he waited – and waited – for Dorothy’s proper biographer to appear.

In 1973, again at the behest of Houghton Mifflin, a second book about Dorothy came out, Marion K. Sanders’ Dorothy Thompson: A Legend in Her Time, the book that persuaded me to write my own. I have no better way to describe the Sanders work except to say that it was inadequate – a cut-and-paste job from Dorothy’s papers that struck me finally as an insult to its subject. Not a moment of warmth or empathy emerged from Mrs. Sanders’ pen, not a minute of drama, not a flicker of passion for a woman whose life was made of little else. I was told later that Mrs. Sanders got the assignment to write about Dorothy from a friend at Houghton Mifflin, who was trying to cheer her up after her husband had died. True or not, the listlessness of Dorothy Thompson was unmistakable to anyone who cared about Dorothy. Internal memos at Houghton Mifflin confirm that they were worried about it also in-house. "The problem with this book is that the author does not like her subject,” said one editor there “-- not one little bit! – and makes no attempt to do so."

So, I took it up. My editor at Little Brown was, as always, skeptical, and my agent feared that no one would care anymore about a journalist long dead, no matter how prominent she had been in her own day. “Try to lift her skirt a little in the proposal,” he advised. I considered it a challenge, something emphatically to avoid. In 1986, after reading and reading, I went back to Europe, subletting an apartment in Paris, and in March of that year I tracked down Dinah Sheean, Jimmy’s widow. She was living in London in a tiny bedsit in Earl’s Court. I called to tell her what I was up to and after a long pause on the phone she said, “Well. You’d better come over.”

Seamless! What grand journey--can't wait to crowd into the London bedsit with you and Mrs. Sheehan. <3

Good God, you are an astonishigly good writer.

This morning I read Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, which always brings me to tears. Then this. People do the same to old Walt. Reduce him to a fragment of their own making.