Ekaterinburg, September 16, 1992

I’m not prepared for the softness of the place. It's too much to call it pretty, but much of it is quiet and gentle in aspect. The town is laid out tidily in squares, and while the evidence of communism's triumph is everywhere apparent -- open ditches, loose strips of metal lying randomly in yards and empty lots, blocks of crumbling stone, numberless tiny windows embedded in scores of junky high rises – there are still old, elegant houses standing in the streets, brightly painted, with the same raised arches and roofline tracery that the Ipatiev House had -- “The House of Special Purpose,” commandeered from a local merchant, where the imperial family were imprisoned and murdered in 1918.

The house was destroyed in 1977 under the command of Boris Yeltsin, President of the new Russian Federation and at that time Soviet Secretary of Construction for the Ural region. The order came from Moscow, of course, after pilgrims began to appear at the site and Western interest in the fate of the Romanovs was fired up again by a book, Anthony Summers’ and Tom Mangold’s The File on the Tsar, which proposed that none of the Romanov family had died in Ekaterinburg, except the Tsar and probably the Heir, Alexei. The Empress and her daughters were purportedly spirited away to another prison in Perm, further west in the Ural Mountains; Anastasia was even seen there, to believe reports, alone, having escaped her captors.

I sat for hours with Tony Summers hashing out this new tale and appeared with him on television as an “Anastasia” expert when his book was published in the United States in 1976. Whatever the merits of the revised account, they were enough to prompt action from the Kremlin, and the Ipatiev House was razed to the ground in September 1977, 15 years ago exactly, an event that Yeltsin now condemns as an “act of barbarism.” He is a native of the region, born not far away in Butka, and rose to power through the machinery of the Ural Soviet. It took three days to knock down the house, leaving only a bare parcel of gravel on one of Ekaterinburg’s main thoroughfares. People still go there to pray; local couples get married on the streetcorner, and a church will soon be built to accommodate visitors and, I suppose, atone for the crime, another astonishment of the post-Soviet era.

Where the Ipatiev House stood. The location of the murder room is outlined by stones on the left.

It was at this same time, in 1976 and 1977, that local citizens first probed the Romanov gravesite. To sort out the mess of its discovery – who got there first, how the burial pit was exactly located, why the operation commenced at all, how it proceeded unhindered under the gaze of the Kremlin – would occupy a book in itself. A skull from the grave, supposedly “the skull of Nicholas II,” was taken to Moscow and kept for a while under the bed of the chief player in the muddle, Gely Ryabov, a “crime writer” and known apparatchik, who waited till 1989 to make the news public. Others in Ekaterinburg will say that they, not Ryabov, were the drivers of the bus and that Ryabov is a liar and a fraud. All of them claimed, at first, that the whole imperial family had been found, which we know now is not the case.

I met Ryabov in London in April 1990, a year after he announced the discovery of the Ekaterinburg bones. The occasion was an overhyped auction at Sotheby's, where, along with an assortment of icons, paintings, and imperial Russian gewgaws, the “Sokolov Report,” records of the White Army’s investigation of the murder of the Tsar, was also up for sale. The catalog spoke of "the spiritual meaning of the event, as well as the human drama, the dignity with which the [imperial] family met their fate and the unusual efforts made by the murderers to cover up all traces of what had happened." Sotheby's Russian expert, John Stuart, spoke of the need for the Russian people to "ask for and receive forgiveness," while Ryabov stood quietly in a corner, surrounded by leather-jacketed companions and entertaining reporters with cryptic tales of teeth and fingers and the “right number” of bodies in the grave. It was "a sad day” for Russia, he told me later; everything was in chaos, everything now was "smoke and fire." Would I come to Moscow? If I came to Moscow, he said, he would tell me everything. But when I got there, he had moved to St. Petersburg and withdrawn permanently from the Romanov case.

“He just made too many claims," a source tells me. He had published pictures of "the Tsar's skull" that turned out to belong to Anna Demidova, the Empress’s maid, and was photographed with another, saying, "This is Alexei's." It was actually one of the girls’. “It simply went too far for him,” someone says. “He can't go back, he can't go forward, he just goes out."

Today, in Ekaterinburg, no one doubts that Ryabov was an agent of the Kremlin. For years he was secretary to Nikolai Shchelokov, Soviet minister of internal affairs and “the worst of an awful lot,” in the opinion of Edvard Radzinsky, author of the bestselling The Last Tsar, published recently in the United States. I’ve met Radzinsky several times, and his American editor, Jacqueline Onassis. Her interest in the Romanovs goes back to her stepfather, Hugh Auchincloss, whose first wife was the daughter of a lady-in-waiting to the Dowager Empress. Later, John F. Kennedy declared outright that the Anastasia case was “the only part of Russian history that really interested him.” Mrs. Onassis paid a lot of money for Radzinsky’s account and has been handsomely rewarded: it is the first in many years to come directly from Russia and even begin to account for the antics of the freelancers in Ekaterinburg who turned up the Tsar’s bones.

Obviously, they were permitted to do so. Ryabov was initially in Ekaterinburg as the writer of a film script about the Soviet police. Then, for unknown reasons, the Kremlin wanted the Romanov grave to be discovered but not, officially, by itself. Rumors were rife several years ago that the bones had been planted in the forest in an effort to mollify the Queen of England, who was said to have declined Gorbachev's invitation to visit Russia until "certain formalities" were seen to. The Queen was understood to mean a decent burial for her Russian cousins, and a public atonement for their terrible end; until that happened, no British monarch would set foot in Russia. It's just one of the stories now told in Ekaterinburg, where conspiracies are taken for granted. My favorite so far is one from the far fringes of rightist thought. "Everyone knows," in this account, that the bones don’t belong to the imperial family, because "everyone knows that the Jews ate them.”

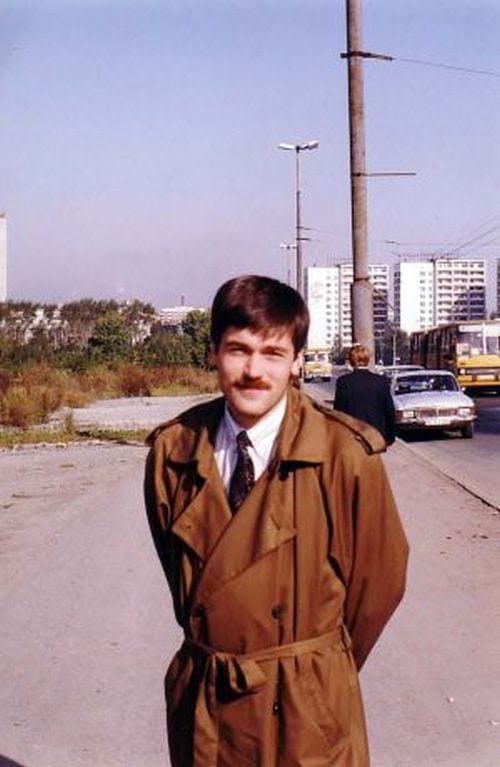

“Legends,” says my guide and translator. “Always legends in Russia!” He is Yevgeny Nagornikh, a handsome man in his thirties, dark-haired, mustached, and with eyes that remind me we are in Siberia; they watch everything intently, smiling but guarded. Yevgeny is well practiced now in discussing the Romanov family. “It is fashionable these days to be interested in the old times,” he says, and is interested to notice, as I do, that everyone who talks about the bones in Ekaterinburg does so from a position of certainty. "Don't listen to him," he mimics, "don't listen to her -- I am the one who knows!" I tell him this is how it always was with Anna Anderson, too, both sides dogmatic and convinced that the others were up to no good. If pigheadedness is a Russian trait, it isn’t uniquely so.

Our driver, Volodya, doesn’t talk at all. “He is angry at life," says Yevgeny, and his face resembles the famous portrait of Sofia Alexievna, the deposed regent of Russia in 1689, scowling in captivity at the Novodevichy convent. I expect to see Volodya’s hair in braids next time, Mongol-style. He plays music in the car that ranges from Western pop (Madonna, Elton John) to some kind of local chanson-y stuff that sounds like it came out of Turkey by way of Henry Mancini. On his dashboard is an emblem of the double eagle, which is imperial, but without the Romanov crown, so it isn’t monarchist per se. “It's the democratic eagle," says Yevgeny, laughing. "After many years of socialism, we are really quite snobbish."

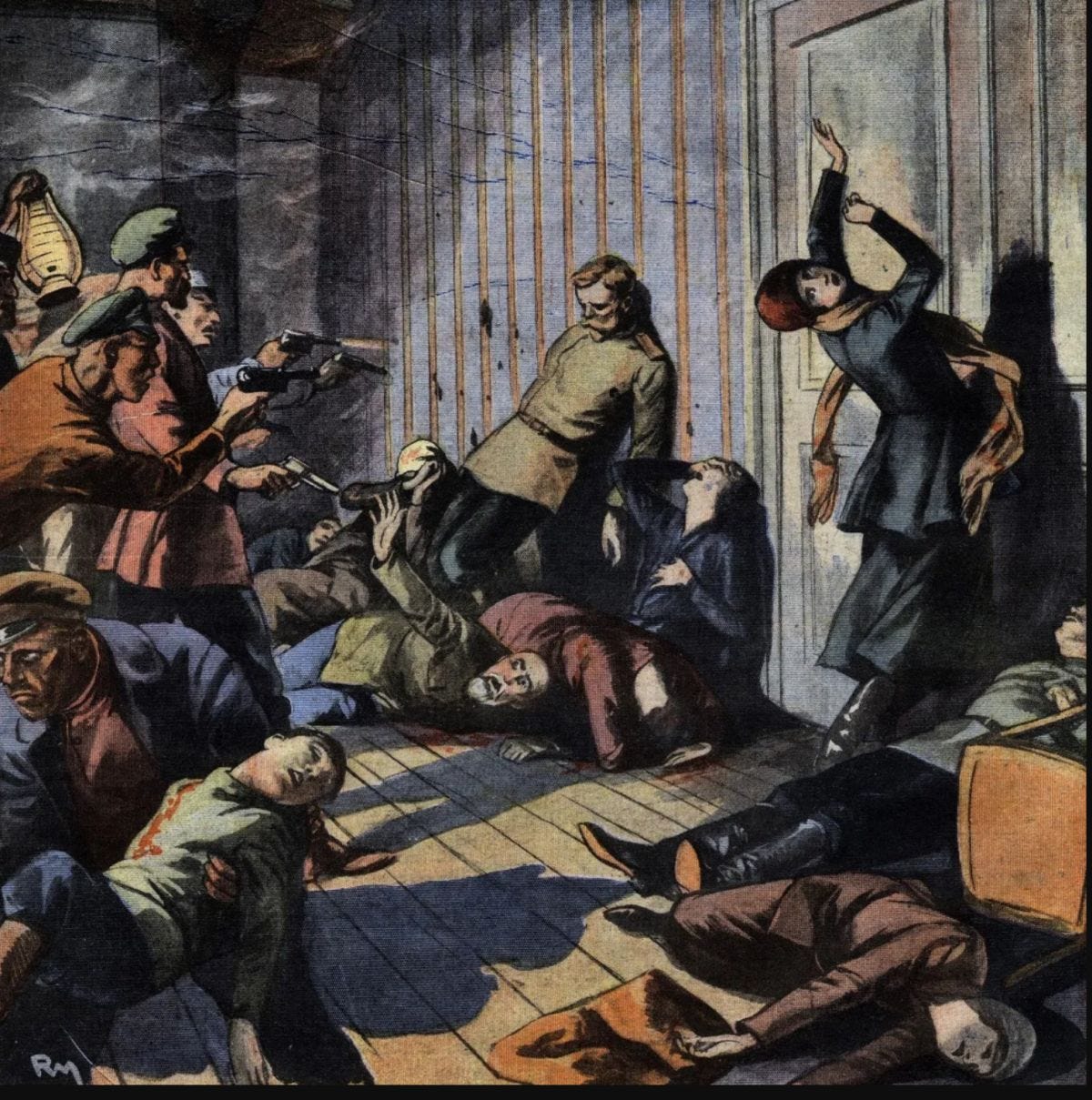

We are standing on the site of the Ipatiev House, where the murder room is outlined on the ground with stones. It is, plainly, a small space, as Summers and Mangold pointed out in their File on the Tsar, only seventeen feet by fourteen, “not enough room for a cocktail party, never mind a mass execution.” Reports released only since the Soviets fell confirm that the dozen or so killers present that night, selected for their hardness of heart, didn’t enter the room until it became necessary to finish off the survivors of the general shooting. They had stood in rows in the doorway and fired over each others’ shoulders. There was no escape from the chamber anyway, which must have been why it was chosen; the grand duchesses struggled to open a locked door against the back wall and failed. No one has explained why the eleven victims weren’t just lined up and shot in the back of the neck, the usual Bolshevik method of execution.

Waiting for emotion, there is none. It’s odd that I don’t feel it in Russia, no affectivity or “vibes” of any kind, not like I do in Germany and England. Certain friends have asked if I think I was involved with the Romanovs in a “previous life” and I say, “No, goddamnit, it’s this life, half of it already.” Twenty-six years on the Anastasia trail could make a cynic out of anyone. I am certainly not a monarchist. A collateral Romanov heir, “Grand Duchess” Maria Vladimirovna, has been throwing herself around Russia lately with her 10-year-old son, a Hohenzollern, in hopes of a comeback. Other Romanovs have put themselves forward in the furtherance of this fantasy, including one who came to Ekaterinburg and prayed in church with his hat on, making a very bad impression on the local population. It seems so childish, so idiotic: Russia goes for strongmen only, and there is not one such in the greatly watered-down Romanov dynasty in exile. "To say the family is divided is a euphemism," one of them said recently. "The family is raving mad."

During the fuss over the imperial family’s remains, the matter of the attendants who died with them has naturally arisen. Moscow wants a state funeral, which would highlight the royals, and Ekaterinburg wants to keep the skeletons together, on site. “Because they died together,” Yevgeny says, “and lay in the pit together for so many years” -- the doctor, a footman, a maid, and a cook. If they are buried traditionally in St. Petersburg, at the Cathedral of Peter and Paul, the bodies will be separated: the Tsar here, the Empress there, the grand duchesses in a corner -- and the servants? Where will they go? “Presumably they are saints as well?” says Yevgeny. “They deserve to be with the people they gave their lives for.”

Did they know they were going to die? Accounts differ on that. The last people to see the family from the outside were a priest, who found them greatly downcast, and some cleaning women who came regularly to the Ipatiev House and reported that “the grand duchesses were laughing. There was no trace of sadness. … Joy showed in their eyes that afternoon.” They were, of course, trained to present a good face to outsiders. But on the night of the murder, according to one of the assassins, the girls were sobbing as they came down the stairs. Certainly, the servants struggled hard for their lives when the general butchery commenced.

We drive to the morgue next, on the outskirts of town. It's a prefabricated building like so many here: white stucco siding, cheap tiles, with that unfinished look they all have. It's as if Soviet builders only kept working until they saw that things could stand up. My friend Brooke Gladstone told me in Moscow, "There's no tradition here of actually getting anything done. It's all busy work."

At the morgue, wild daisies are growing at the door, and a sign says, "Families may collect their corpses daily from 9 to 5. Closed on Sundays." The bones are off limits to visitors, but for a discreet sum we can see them through an open door, lying on tables. I don’t need more than that. They look just like their pictures. Yevgeny mocks the coroners’ instructions: "It is officially forbidden for anyone to take photographs of the skeletons, and especially to sell them to foreigners.” Unofficially, he says, “they are sold everywhere."

Volodya is asleep when we get back to the car. It takes a lot to wake him up. He shows no interest at any point in where we're going or why. He is a worker, says Yevgeny, and for the moment still king in these parts, the Red Urals: “We can't afford to offend him.”

September 17, 1992

The grave is in a wide-open clearing in the woods, just as the reports say, about 200 meters from the railway line. The ground is muddy; we are near a swamp. A marsh with cat tails is growing 50 feet away. The pines are fewer here and the birches more, their leaves golden and hanging down, like willows. It is beautiful, it is "Russian." There are ruts and tire marks everywhere, and a wooden cross, high, made of simple logs and taller than the one erected at the Ipatiev House. It presides over a dirty hole filled with water.

I can't help thinking that this is an unlikely place to have buried them. I don’t dispute it, but it doesn’t make sense. It's too open, too visible. It's hard to see how the Bolsheviks could have concealed it so well. You would think that signs of recent digging would have been easy to detect, particularly since, within days of the murder, everyone in Ekaterinburg was looking for the bodies. The White Army scoured these woods for more than a year. The choice of this space verifies without any doubt that the Bolsheviks, at the end, were rushed, in a hurry to get rid of the corpses.

On the other hand, during the whole time we’re here, no other person passes by on the road or in the woods. And again that mist, the soft white pollution -- when we head back to Ekaterinburg someone says, "Let’s get back to the city for some fresh air." We were thick in the trees at that moment, looking out on a distant field of cows and sheep.

I’m at the grave with Yevgeny and the archaeologist who formally excavated the bones: Ludmila Koryakova, blonde, pretty, looking like Lana Turner, only natural. There is nothing glitzy about her. She is competent, brisk. Her full title: Doctor of Archaeology, Laboratory of the History and Archaeology Institute of the Urals Science Center of the USSR Academy of Science. She seems suspicious. She’s been burned already by the press, in particular, by the Sunday Times in London, which recently published a huge article on the Romanov discovery and stole a lot of her material. She is trying to have published her own account of the excavation and asks if I will help her do that. She gives me a fat envelope, some kind of proposal for her story, to copy and post to editors when I get back to New York. She makes me promise to do it and I have. I don’t doubt her rectitude in this matter and so far, she’s the only one.

It was on July 9 of last year, says Koryakova, in 1991, that top officials of the regional administration ordered her to excavate “an unknown grave from the Soviet period" in the forest outside Ekaterinburg. Her specialty is in prehistoric settlements of the Western Siberian and Ural region and normally she digs with an eye to those, specifically for ancient findings.

“Why me?” she asked.

“Someone advised us to phone you,” came the answer. There is always "someone" behind the scenes in Russia, “someone” giving the nod. Koryakova refused to go forward until commanded to do so by her superiors at the science academy. She was practically marched into the forest to begin the work. Now she shrugs her shoulders: “Everything was secret, secret.” She has no use for that, she says, for the need of concealment. She thinks it’s ridiculous.

"I didn't want to participate," says Koryakova, “for many reasons,” chief among them a complete lack of preparation for the task. Everything was put together "much too quickly." It surprised her, because normally in archaeology the order is reversed: too much time is taken. But this dig had to be done at once, apparently, on the spot.

“There was nothing like the proper atmosphere, no tools, no instruments. We had just one big digging machine, some military trucks, and several spades." When Koryakova challenged these conditions "in a very stern manner" -- I may conclude that she gave “someone” what-for -– the order came down that everyone present should start to dig, no matter their expertise, “a catastrophe,” she says, for the integrity of the site. There were fences and klieg lights around the pit, and the most bizarre company of helpers on the job — “two of everything, like Noah's ark: two police colonels, two detectives laden with cameras and video equipment, two forensic experts, two epidemiologists, the town procurator and his secretary, and two policemen with submachine guns."

Everyone took a shovel and dug: the colonels, the detectives, the procurator, and Alexander Avdonin, a local geologist who had worked with Gely Ryabov during the first excavations in the 1970s and who now heads an organization in Ekaterinburg called Obretenie — the word translates loosely as "recovery" and has deep religious overtones. The announced goal of Obretenie is "to restore the morality of Russian history." The actual plan, says Koryakova, is to create a memorial on the site of the grave, with a park around it and an office for Avdonin on Resurrection Hill, the finest address in Ekaterinburg. It isn't possible any longer to sort out the details of Avdonin's association with Gely Ryabov — Ryabov isn't talking, and Avdonin reacts badly, as I can attest from an interview with him yesterday, whenever it's suggested that he wasn’t the prime mover in the hunt for the bones. He is "a very strange, very strange man," Koryakova says, “and he doesn’t really know more than anyone else” about the Romanovs and their grave.

Yes, she continues: the amateur excavations of the 1970s "considerably destroyed" the gravesite and the material evidence. The skeletons were no longer lying in the way they were dumped. “Some bones were destroyed.” She thought at first that the corpses had been dismembered, but later concluded, no, they've only been moved. I ask and she assures me, however, that “these bones have always been in this earth.” In other words, they weren't brought here lately from somewhere else. Some of the victims were shot while lying down. Their faces were smashed to prevent recognition. The remaining bones were in such bad shape they could hardly be distinguished from the surrounding soil. If bits and pieces were left in the mud, it's not to be wondered at: the excavation was completed in three days when it should have taken weeks. Koryakova has seen a lot of burial sites, turned over lots of bones, "but never so many that were so badly damaged" -- so “violated,” she says. "I was ill. It was a terrible picture."

But were they the Romanovs? Koryakova thinks so but can’t affirm it. There are bodies buried in unmarked graves all over the Ural region: victims of the revolution, of the famines, of Stalin and the camps. Witnesses speak of "untold horrors" in Ekaterinburg precisely at the time of the Romanovs' detention there, in 1918, as White Army troops menaced the Bolsheviks from the east and drove them to a frenzy of killing. When Isadora Duncan came to dance in the city in 1924, at the invitation of the Soviet government, she wanted to have her hair done for an evening performance and couldn’t find a hairdresser anywhere in town. There weren't any "ladies" left living there, she reported. “They shot 'em all.”

Koryakova strides around the clearing while she talks, ranging into the woods, in wide arcs, as if sniffing for something. She says the area "looked a lot better" last year, but so many people have been poking and digging around since then that it’s lost any integrity it might have had. She doesn't think there's much chance of finding the missing children, Anastasia and Alexei: "The natural condition of the soil is very bad here, very acidic. There are marshes everywhere." She says it’s "vitally important" that I tell the world about the "problems and discrepancies" still abounding in this case, and that these can be traced in large measure to the "completely unprofessional" way in which the excavation was conducted.

For myself, I’m convinced the lingering mysteries can be explained by the two missing bodies. This is why the Romanov corpses had to be removed from the mineshaft; this is why the story of a second bonfire was made up to account for extraordinary sloppiness. Koryakova agrees this is likely. She says if the Bolshevik soldiers were drunk, confused, fighting, or whatever, and that two bodies were then found to be gone, they would have to have done something to justify it, and it wouldn't be something that reflected their ineptitude, or their treachery. Yesterday she was at the morgue where the bodies are kept -- on a completely different case, she says, although I wonder if she wasn't getting material for her own article -- and remarks that the doctors there assured her, according to all they know so far, that Anastasia is the missing grand duchess.

We go home by back roads and I see small wooden cottages with nicely, even gaily painted shutters and eaves. Cows are mooing. Potatoes and onions are being dug.

At the grave: Koryakova, Volodya, and Yevgeny Nagornikh.

"My God, Russia. Who will ever understand it?" -- Dick Nixon

Thanks so much. This is important testimony. Again, fascinating.