Ekaterinburg, modernized and cleaned up. The cathedral sits on the site of the house where the Russian imperial family were murdered in 1918

September 15, 1992

I’m in Ekaterinburg on assignment for Vanity Fair. Tina Brown didn’t want to cover the Romanov story but her successor as editor, Graydon Carter, sees potential in it and has sent me to Russia to report on the bones. I arrive in town at two a.m., at the mercy of Aeroflot, which has canceled multiple flights from Moscow already before putting me on a plane with broken seats. They don’t stay upright, flopping back and forth for most of the trip. No one aboard pays any attention to the instructions of the flight attendants. This is normal now, if it wasn’t before, every man for himself.

I’ve been in Moscow already for several days, talking with government specialists who are working on the Romanov case. Dr. Vladislav Plaksin, Chief Medical Examiner of the ex-Soviet Union, was last year given the task of coordinating the investigation of the Ekaterinburg relics at the national level. It’s a job he never wanted. I meet him in his office with a number of other doctors and forensic specialists, some of whom have sold their stories to the press.

“There has been too much talk,” Plaksin insists, too much sensationalism: "There have been intrigues." His life has been turned upside down by the international media, which jumped on the story of the Tsar's remains and "garbled everything," and by “mischief” in Ekaterinburg, where a bizarre assortment of politicians, apparatchiks, geologists, and freebooters have kept the pot boiling since the grave was opened in 1991 and will share their findings with anyone who asks. To believe Plaksin, they have even sold off chips of the bones to curious reporters and others. I am to understand that Moscow’s relations with “these amateurs” have deteriorated greatly. Apart from the matter of the bones themselves, there is a longstanding, almost traditional animosity between the provinces and “the center,” Moscow, which in this case has sharpened to a point. The skeletons are still at the morgue in Ekaterinburg and Ekaterinburg means to keep them there. It has been “difficult,” Plaksin says, “very difficult” to proceed.

Even so, after months of negotiation, nine femurs, one from each of the Ekaterinburg skeletons, are headed to England next week for DNA testing by the Forensic Science Service at Aldermaston, in cooperation with the British Home Office and under the sponsorship of the BBC. Nothing can quell the public’s interest in this story. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, the Queen’s husband and a grand-nephew of Empress Alexandra, will provide a hair sample to identify at least the female skeletons through comparison of DNA. Plaksin regrets the need to move any part of the inquiry out of Russia and complains especially that a foreign television network will be footing the bill. Until the bones are examined by “proper Russian experts,” he declares, they are only “supposed” to be those of the Romanovs.

Apart from that, Plaksin knows nothing about Nicholas II and his family. None of them do – they are in diapers. Under the Soviets, Russians weren’t just uneducated but anti-educated about their former rulers. In photographs, they can’t tell one grand duchess from another, one uncle or aunt, one general or lady-in-waiting. They know and like Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, and Alexander II, the “Tsar-Liberator,” who freed the serfs. They recognize and laugh at the figure of Rasputin. They know the name “Anna Anderson” but regard the Anastasia story as a Western “concoction,” meant to extort money and crown treasures from the Russian people. When I point out that -- according to American forensic experts brought to Ekaterinburg last year to study the bones – Anastasia’s body is still missing, I am greeted with spit and spatter about “fairy tales” and foreign meddling.

"You are not Russian,” I am told. It’s their answer to everything: “You are not Russian.” Ekaterinburg’s unilateral decision to bring in foreign experts has been especially contentious: “It is the equivalent of asking the KGB to help investigate the murder of John F. Kennedy,” one of the American scientists admits.

In truth, at this point, and with the skeletons still in Siberia, there is little for anyone in Moscow to do. One doctor wants to examine boxed-up clothing of the imperial family, kept at their palace at Tsarskoe Selo, hoping to extract DNA from sweat stains that might have been left on them. Another, drunk in his office, digitally reconstructs faces from photographs of the Ekaterinburg skulls and tells me that not Anastasia but Maria is the missing daughter. I see how this story is being constructed to suit the needs of politics and national pride. At every level, in every office, are a runner and a secretary, sitting silently, staring ahead, hands in their laps. They are all in the dark.

Riding into Ekaterinburg from the airport, even at night, I see a fine mist in the trees, a soft white blanket over everything. It looks beautiful but turns out to be smoke, or worse, the belch of innumerable stacks from factories in the region. I’ve been warned that the air in Ekaterinburg is terrible for your lungs. It was a “closed city” under the Soviets, a military-industrial center inaccessible even to most Russians without a permit. Renamed Sverdlovsk in 1924 -- after Yakov Sverdlov, the high Bolshevik who supposedly gave the order to shoot the Tsar’s family -- it is also the town where American U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers was shot down on a spy mission in 1960. If the place is known in the West for anything but regicide, it is for Powers’ two-year ordeal as a prisoner and his dramatic exchange for a Soviet spy, Colonel Rudolf Abel, at three in the morning on the border of East and West Berlin. It was the ultimate Cold War moment, solemnized a few years ago in Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies.

But the Cold War is over, according to experts, and I’ve arrived in a city that took its old name back as soon as the Soviets fell. Ekaterinburg. It resounds in history -- someone has said this before -- with a sickening peal of evil, and the scant records of the weeks the imperial family spent here -- hot, stifling weeks of midsummer -- have nothing in them to lighten the impression of doom. In all the years I worked on Anastasia, I never expected to be here, in this place, alone at two in the morning.

“Peter Kurth?” I am greeted at the door of my hotel by what is evidently the manager, a shrewd-looking man of uncertain age, whom I fantasize might keep a Mauser in his jacket. He looks in my eyes and says, “You are famous in Ekaterinburg.”

Did I choke? Turn pale? I know that I am speechless for a moment. But it’s not a sentence of death being read. Vanity Fair has made multiple reservations in my name, apparently, and I’ve failed to show up for three of them already. Hotels for tourists are new in Ekaterinburg; until last year, no one came here from the outside. I was advised to bring chocolates with me, coffee, and cigarettes, and indeed they are swelling my suitcase now. I answer the manager’s greeting by handing him a carton of Marlboros. How can I be here?

The room is spare: a bed, a table, a lamp. At breakfast there is nothing to eat but bread and stale cheese, at dinner a kind of goulash that might have anything in it. Wall sockets fall out in my hand when I use my adaptive plugs. There is no toilet paper. I left a dozen packets of Kleenex in Moscow – why? I think of the first investigation into the murder of the imperial family in 1919, when the White Army held the town and scoured the area for Romanov remains. “The world will never know what we did with them,” said a satisfied Soviet. A page from a medical textbook was found in the forest, apparently used as “lavatory paper” by one of the soldiers getting rid of the corpses. It was included in an assortment of imperial relics I saw a few years ago at an auction in London. How can I be here?

In the fall of 1970, my brother went to Yale, during my last year of high school, and at Christmas brought me a library copy of Nicholas Sokolov’s Enquête judiciaire sur l’assassinat de la famille impériale russe, published in Paris in 1924 and unavailable to me in Vermont. For years this book was the bible of Romanov-murder studies and I felt grown-up having it in my hands for the first time, even on short-term loan. Sokolov was the magistrate appointed by the White Army in Siberia to determine the fate of the Tsar’s family. His conclusions were definite: they had all died in the small cellar room where they were shot, their bodies taken to a pine forest outside town, hacked to pieces, doused in sulfuric acid, and burned on bonfires. What remained was tossed down an abandoned mineshaft, one of many in the region, and left to be discovered.

It was a preposterous story, yet few had trouble accepting it. There seemed to be no other explanation for the complete disappearance of eleven people: the Tsar, the Empress, their children, and four attendants, unlucky enough to be trapped with them at the end. Small icons and smashed jewelry were found around the opening of the mine, along with scraps of burnt clothing, as if beckoning to be recognized. A severed finger and a murdered dog that had belonged to one of the grand duchesses added weight to the tale, even though they hadn’t appeared at the mineshaft until many months after it was first examined.

Inspector Sokolov, a minor official and pious Orthodox, was apparently also a sap, wholly instructed and guided by military leaders in the midst of civil war. We may assume that evidence was planted at the forest mineshaft for effect, either by the Bolsheviks, in order to distract the Whites from the true location of the Romanov grave, or by the Whites themselves, desperate to prove something while they still had the time. Their goal was to cast further opprobrium on the Bolsheviks, if any were needed, and to smear the Tsar’s assassins as “Jews” in service to the Protocols of Zion, by far the ugliest lie attached to a legend already spreading dubiously around the world.

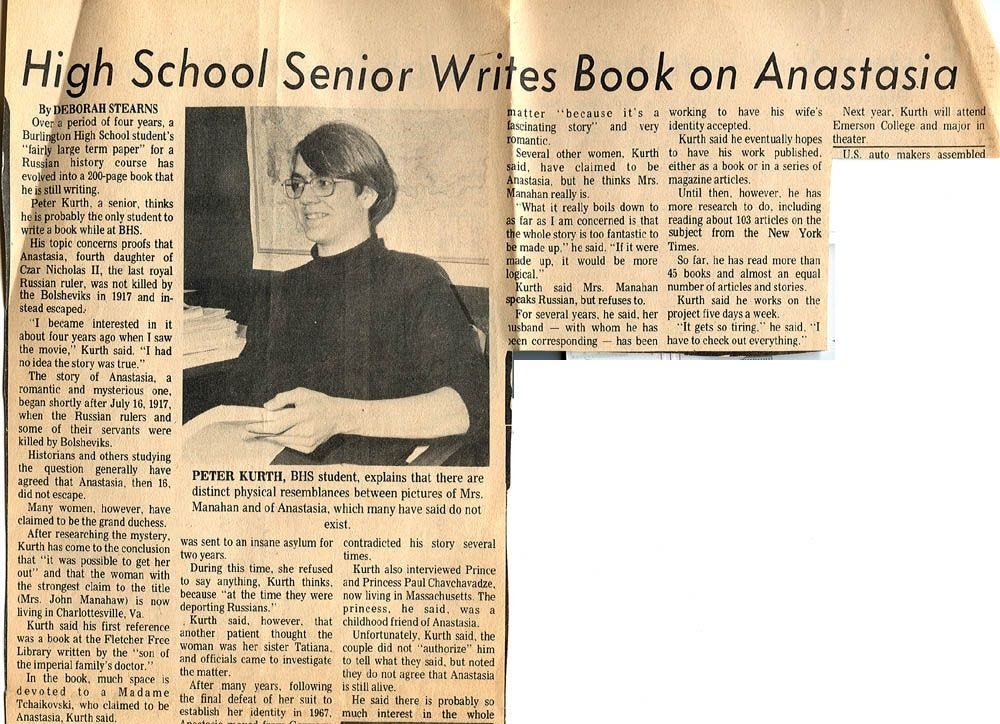

That same fall, in 1970, as a senior in high school, I completed what turned out to be the first draft of Anastasia, a 200-page mimeographed diatribe in favor of Anna Anderson that I had produced for a Russian history class. I was already far gone in my obsession. In February of that year, on the 50th anniversary of her suicide attempt in Berlin, the West German Supreme Court had declared Mrs. Anderson’s case “non liquet” – legally unresolved – and it seemed to me obvious what that really meant. No claim of this kind could have gone so far, I reasoned, without substance behind it. The chief judge at Karlsruhe even called Mrs. Anderson “Anastasia” when reading the verdict. I remember standing in my room with a copy of I, Anastasia in my hands, the claimant’s ghosted autobiography, where I saw again the reports of doctors, nurses, psychiatrists, lawyers, companions, and royal cousins who had attended her through the years and had concluded with Princess Xenia, in different words, the unassailable fact: She was herself.

Anna Anderson in Bavaria, 1926. Her left arm remained paralyzed after surgeries for bone tuberculosis.

“I maintain that it is absolutely impossible,” said one, the director of a sanatorium in Bavaria, “that this woman is deliberately playing the part of another, and [further] that her behavior, when observed in its entirety, does not in any respect gainsay that she is the person she says she is.” Another, the psychiatrist Karl Bohnhoeffer, father of the famous Pastor Dietrich Bohnhoeffer, saw Mrs. Anderson in Berlin and rejected the notion that she was pretending anything: “It has been asked if there can be any question of hypnotic influence on the patient by some third party. This is to be denied, as is the other supposition that this is a deliberate fraud.” Several in the Romanov family believed that a “substitution of souls” had taken place, a “transmigration,” such as to endow Mrs. Anderson, whoever she was, with Anastasia’s complete character and personal traits. That the Tsar’s sister Olga, having already dispatched former servants and attendants of Anastasia to meet the claimant in Berlin, finally went herself on the strength of their reports, struck me as impossible from the beginning unless the claim had merit. Why did they go back? Why did they keep going back? It hadn’t happened before and it wouldn’t happen again, not for any Romanov pretender. Olga wrote to Mrs. Anderson on returning home:

I am sending you all my love, am thinking of you all the time. It is so sad to go away knowing you are ill and suffering and lonely. Don’t be afraid. You are not alone now and we shall not abandon you.

But they did abandon her, ran for cover, and slammed their doors. Instructions had come down from somewhere, plainly, and there was no road to appeal. When asked under oath to explain what had happened, Olga replied that she “didn’t remember,” only that the decision was final and never brought up again. “It was not the custom in our family to discuss things overmuch,” she said. This sudden change of heart might not have impressed me so strongly if the witnesses hadn’t been so adamant. All of them used the same scripted words: “We affirm categorically that this woman bears not the slightest resemblance to Grand Duchess Anastasia, not in manner, feature, or personality.” Why such harshness? Why the obvious lie? It convinced me straight out that she was real. And right there, looking at her fake autobiography for the umpteenth time, I became an Anastasian. I took up the sword without doubt or hesitation. I would be Anna Anderson’s avenger.

Of course, I was still a child. In 1970 my parents were divorcing and I suppose Anastasia became a buffer against the confusion and sadness I must have felt. I knew that I occupied the same position that Anastasia had in a family of five children, fourth down in the row, and knew also that I stood out, like her, as a clown in the family circle, often obnoxious and a bit of a brat.

“She was a nasty little girl,” said Princess Nina, remembering childhood scuffles and orders from a tsar’s daughter, higher in rank, to stand down. “We were exactly the same age and she was jealous of me because I was taller than she was.” I felt so close to it all when I heard these stories. “It was like talking to people who had known Marie Antoinette,” as Brien said. That summer my heart had been broken by an older man who took me to bed with him, had his pleasure for several months, then left me on my own. I was 17, Anastasia’s exact age when she faced her assassins. I didn’t know if I was straight or gay and was hugely troubled by it. I kept a journal of my worries and woes, my secrets, my adventures with the lovers, male and female, I began sleeping with at that time. I noted all the days I smoked pot, which were many. I was working at the university theatre as an apprentice, and it was there I found purpose and affection in the arms of older people. At school I was indifferent, grading well when the subjects interested me and not when they didn’t. I had many friends but was a nerd by anyone’s estimation.

In the spring of 1971, I went to Yale myself, not as a student but as a researcher. I was let out of high school for an independent-study project and would keep having them when I went to college, first in Boston, then in Vermont. Everyone knew that Anastasia was my thing and that nothing could turn me away from her. After my graduation in 1975, I went to Europe and studied more. I had learned German and French to read the massive court records and hundreds of newspaper articles Anna Anderson’s case had generated over time. I wrote and revised texts that got fatter and fatter as I went on. A friend secured the attention of a big agent in New York, top of the line, who wrote to me in 1977, “You have a fascinating manuscript here,” asking if she could represent me. I fled to London – I wasn’t prepared to present myself with confidence. I drank all the time. Finally, I got married and wound up working as a clerk in a Vermont bookstore. “For crying out loud, Pete,” a friend remarked, “you’re 25 years old and still working on that goddamned book! You’ve got to move on!” It hit me hard. I didn’t know then how stupid the advice was.

I’m looking at it now: Anastasia: The Riddle of Anna Anderson. My name is on the jacket along with my first author’s photograph, a heavily bearded, scowling face that was meant to ring bells about Russia and Rasputin. I was about to give it up before I finally got a publishing contract in December of 1980. I’d had a dozen rejections by then, maybe more, from major houses in New York. I’d had two literary agents, both of them prominent in the trade. My father said to me at one point, “Son, if you do nothing else but write it and it just sits there on a shelf, you’ll have accomplished something. We’re proud of you.”

Those may have been the words that gave me incentive to go on. In May 1980 I took Anastasia out of the drawer for what would be the last time. There were no computers then -- a “drawer” was the only place you could hide a manuscript in your humiliation and despair. I told myself, “I’m gonna whack this thing into shape if it kills me, and if I don’t have a publisher by the end of the year, I’m never going to look at it again.”

At the eleventh hour, the phone rang. An editor at Little, Brown wanted to see me in Boston. “Get down there now,” said my agent. And I did. And somehow it worked. Why they took a chance on me I still don’t know. But on December 19, 1980, 12 days before my self-imposed deadline, I was told that the deal was done. Little Brown wanted the book. I was either so excited or so stunned by the news that I forgot to ask about the advance, how much money I would be given to continue.

“Don’t you want to know?” my agent asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “I guess it would be good to know.” But it really wasn’t the first thing on my mind.

Mesmerizing! Addictive. Hard to believe you were so young and already so brilliant. Keep it coming Peter! 💕

Peter Kurth, You are my hero. That you were a survivor of child sexual abuse makes your achievement all the more heroic... a survivor standing with another survivor. Bless you.